1st Republican National Convention, 1856 |

| |  |  |  |

| Temporary Chairman | Permanent Chairman | Presidential Nominee | Vice Presidential Nominee |

| Robert Emmett NY | U.S. Sen.

Henry S. Lane IN | Former U.S. Sen. and General

John C. Fremont CA | Former Sen.

William L. Dayton NJ |

Formation of the Republican Party

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 was the single greatest error of the Pierce Administration. The ascendant Democratic Party was aligned in support of slavery and pushed through an effective repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850. The North, which already felt that the South had received the better end of the Compromise of 1850, believed they had been betrayed. Anti-slavery northern Democrats left the party. New political parties developed locally out of the disintegrating Democratic and Whig Parties. These disaffected groups organized themselves into anti-administration state groups, including the Anti-Nebraska Party in Ohio and the People's Party in Indiana. On 3/20/1854, a gathering in the Little White Schoolhouse in Ripon WI organized a new anti-slavery party with the name of the Republican Party (though other locations also make the claim to be the party's birthplace).

The success of the Republican Party in 1854 was notable but not overly impressive. Their first major victory came in the Maine state elections on 9/11/1854. The Republicans ran on a ticket of American Party candidates for statewide offices and Republicans for U.S. House. The Republicans won five of the six congressional districts. They then went on to win seats in IL, MI, and WI on 11/7/1854 for a total of just 13 seats. By contrast, the Anti-Nebraska Party won 21 seats. The greatest success of the party was winning the governorship in Michigan. By the beginning of 1855, the opposition party throughout the nation was the American Party, including CT, NH, and RI.

The Republican Party continued to make gains in 1855. When the national Know-Nothing convention approved a platform endorsing slavery, a large contingent of northern delegates bolted. These "Know-Somethings" approached the Republicans and began to hold joint anti-slavery and anti-secret conventions [NYT 6/15/1855]. The Anti-Nebraska Party in Ohio officially joined the Republicans, a major boost to the nascent party. in the 1855 elections, the Republicans picked up the governorships in Wisconsin, Vermont, and Ohio, though the governor of Maine, who had switched to the Republicans, was defeated. A special election for the U.S. House in Vermont on 1/3/1856 set the stage for the presidential campaign. There, the Republican nominee collected the endorsements of the anti-administration parties in the district and took the seat with 80% of the vote.

The Republican Party was organized nationally on 2/22/1856 in Pittsburgh. Party leaders meeting during the deliberations on selecting the Speaker of the U.S. House issued a call for a national organizational convention to be held in Pittsburgh on Washington's birthday, signed by five Republican state chairmen. The convention organized the Republican National Committee at the same time that the American Party National Convention meeting in Philadelphia divided in half. The Republican convention issued a call for the first Republican national nominating convention, to be held in Philadelphia on 6/17/1856. The address carefully avoided the word "Republican," instead calling for a gathering of delegates opposed to the extension of slavery.

During the spring of 1856, Republican state conventions were held in the free states to choose delegates to the Philadelphia convention. One of the first was Maine on 5/7/1856, which selected delegates pledged to Fremont [NYT 5/8/1856]. He had written a famous anti-slavery letter which appealled to anti-administration politicians throughout the North.

As the states held their conventions, news of bloodshed in Kansas spread via the newspapers, fanning the anti-slavery flames. Furthermore, the North American Party was holding its national convention in New York City just as Republicans gathered in Philadelphia. Agents of the NAP were on hand in Philadelphia, urging a joint ticket [NYT 6/17/1856].

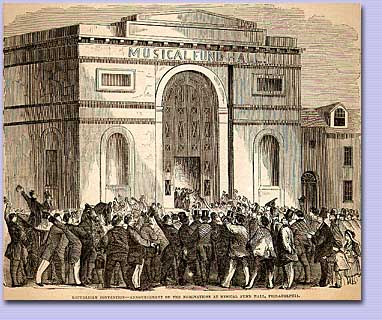

The Convention Site, the Musical Fund Hall of Philadelphia |

|  |

Woodcut of the Musical

Fund Hall, 1856 | Musical Fund Hall

following 1891 renovations |

First Republican National Convention, 6/17-19/1856

The first Republican National Convention assembled in the Musical Fund Hall at 808 Locust Street, Philadelphia. The building was a former Presbyterian church house, renovated by William Strickland in 1824 to its appearance at the time of the convention. The building was later remodeled in 1891 by Addison Hutton, who added a third floor and redecorated the interior with Victorian motifs. The building was converted into apartments in the 20th century.

Altogether, 567 delegates were present. They represented all the Free states and three slave states (KY, DE, and MD). Each state was entitled to three delegates for each electoral vote it had.

The text of the convention proceedings is posted here.

Edwin D. Morgan, national chairman, called the convention to order at 11:00 a.m. on 6/17/1856. He began his address to the delegates by saying that "you are here today to give direction to a movement which is to decide whether the people of the United States are to be hereafter and forever chained to the present national policy of the extension of human slavery."

The temporary chairman and keynote speaker, judge Robert Emmet of New York, outlined his view of the slaveocracy control of the Democratic Party and how the newly chosen Democratic standard bearer, James Buchanan, had proven himself to be aligned with the slave interests.

Following Emmet's speech, the convention proceeded to organize. It appointed a single committee on credentials and rules rather than the normal two committees. It then passed a resolution that the national ticket not be chosen until the adoption of the platform. The Free Soil delegates to the 1848 Democratic National Convention were seated as honorary delegates.

The second session began at 4:00. Henry S. Lane was announced as the permanent chairman. Contests were raised in Pennsylvania, which was amicably settled. The Kansas delegation was given voting status. After a speech by Henry Wilson, in which he set forth the qualifications of some presidential aspirants, the convention adjourned for the evening.

Judge David Wilmot introduced the platform at the beginning of the second day. It stated that Congress had sovereignty over the territories, called for the establishment of a free state in Kansas, advocated ending polygamy in the Utah Territory, called for a transcontinental railroad, and critiqued the record of James Buchanan. In particular, the platform said that Buchanan's Ostend Circular (advocating taking Cuba by military force) "was in every respect unworthy of American diplomacy." The platform was adopted with a minor change.

The Presidential Nomination

After the platform was adopted, the convention waffled on how to proceed. One delegate recommended an informal vote for President, but other delegates objected and asked for more time to consider their options. During the discussion, Seward, Chase, and McLean withdrew from contention. The convention voted to hold an informal ballot and adjourned to allow the delegates to weigh their options.

When the convention assembled in its evening session at 5:00, Edwin Morgan told the delegates that the North American Party had contacted him and wanted to nominate a joint ticket. U.S. Rep. Joshua R. Giddings objected to a joint ticket with the NAP. He argued against nativism and believed that foreign-born citizens had every right to participate in the Republican Party. The convention agreed with Giddings, whose Ohio delegation included some Know Somethings of 1855.

The informal ballot took place next. Ohio was recognized to place McLean back in contention, then the states were called in the traditional order beginning with Maine. Fremont won 63% of the delegate vote. McLean won a band of states along the border with the slave states, stretching from New Jersey through PA, OH, IN, and IL. Fourteen delegates did not vote, and there were four scattering votes.

After some wrangling about the North American convention, the convention proceeded to the formal ballot for President. McLean's delegates mostly switched to Fremont, though he kept 37 in OH and PA. Fremont was thus officially nominated for President.

| Presidential Balloting, RNC 1856 |

| Contender: ballot | Informal | Formal |

| John C. Fremont | 359 | 520 |

| John McLean | 190 | 37 |

| Abstaining | 14 | 9 |

| Others | 4 | 1 |

Vice Presidential Nomination

When the delegates gathered on the last day of the convention, the first item of business was choosing a vice presidential nominee. Delegate Edward Whelpley gave the first nominating speech at a Republican National Convention, placing William L. Dayton in contention. John Allison of Pennsylvania nominated former U.S. Rep. Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. Others placed in nomination were Wilmot and John A. King of New York. On the informal ballot, Dayton received 55% of the delegate vote. Lincoln carried IL, IN, CA, and NH to place second. The formal ballot followed, in which Dayton won 94% of the delegate vote.

| VP Balloting, RNC 1856 |

| Contender: Ballot | Informal | Formal |

| William L. Dayton | 253 | 523 |

| Abraham Lincoln | 110 | 20 |

| Nathaniel P. Banks | 46 | 6 |

| David Wilmot | 43 | 0 |

| Charles Sumner | 35 | 3 |

| Scattering | 80 | 15 |

During the vice presidential voting, the North American convention was discussed again. The Republicans maintained that an alliance with them would hurt their chances, so they took no action on the NAP communication.

The convention took some minor actions regarding organization of young Republican clubs around the nation and then adjourned sine die.

2d Republican National Convention (1860)

Popular Vote of 1856

Electoral Vote of 1856

[Less...]